Engage, Excite, Motivate with Gamification

Anita Knox

Abstract

The pandemic forced educators to quickly adapt classroom curriculum and techniques to an online remote environment. Some students succeeded and preferred the flexibility of online learning. As face-to-face class resumes, a new normal has emerged. School districts are investing in a permanent virtual presence for fully online and hybrid learning. The opportunities posed by remote online learning also come with costs. Challenges include learning declines with some students lacking motivation to participate in remote learning. This may be addressed by designing curriculum specifically for remote learning. One solution in motivating students to log into the classroom and maintaining that engagement is gamification. Successful integration requires a design that aligns game mechanics with learning outcomes. This paper offers a design model that can be adapted to a variety of learning interventions and audiences. Game mechanics will be discussed, along with an example design.

Keywords

Gamification, remote learning, online learning, motivation

Introduction

A renewed focus has been given to remote learning. The pandemic required schools and businesses to quickly pivot from live course delivery to remote using online classrooms. Moving forward a new normal has materialized, which includes the continuation of online remote learning and hybrid models in addition to a return to the classroom. The flexibility enjoyed by students and parents make remote learning an attractive option for future education (Superville, 2020). Some learners succeeded in the remote environment, motivating the build out of long-term solutions to what was thought to be temporary (Singer, 2021). Numerous school districts continue to establish a virtual presence even after a return to the classroom (Singer, 2021). School district leaders were surveyed by RAND Corporation. Findings indicated twenty percent of school districts surveyed said they were planning a permanent fully remote school and planned on continuing some level of remote learning even after the pandemic ends (Superville, 2020). Ten percent planned to have some version of hybrid or blended learning, which would combine days of remote learning with days of face-to-face classes (Superville, 2020). Although remote learning has benefited some students, it was not successful for all. There are some concerns that the remote learning of today will foster lower achievement experienced during the pandemic (Singer, 2021). However, practices like delivering classroom content online can be addressed by designing a learning experience specifically for remote learning. Another common challenge associated with remote learning is a lack of motivation by students to log into a classroom (Superville, 2020). Educators are faced with finding more innovative ways to remotely motivate, engage, and influence achievement of learning goals.

One opportunity to address these challenges is integrating gamification (Mora et al., 2017). Gamification is commonly defined as using game elements in a non-game context (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016; Kim & Castelli, 2021; Brull & Finlayson, 2016; Simões et al., 2013). Kopcha et al., (2016) adds on to this definition with integrating game principles into a learning environment.

A commonly identified benefit to gamification is motivation (Klock et al., 2015). Younger students have grown up with video games, this form of entertainment has always been part of their lives, making it a natural motivator for classroom integration (Simões et al., 2013). Kim & Castelli (2021) studied gamification motivation across ages ranging from childhood through older adults. Although all ages experienced some level of motivation, older adults and younger students showed a high level of interest. In addition to motivation, studies identify that gamification has the potential to influence achievement, emotional interaction (Kopcha et al., 2016), engage learners, and improve retention (Brull & Finlayson, 2016). The reward mechanisms stimulate a basic need for a feeling of accomplishment (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016).

Despite the benefits, designing a gamified learning experience can be cumbersome (Mora et al., 2017). Game mechanics require alignment with learning goals, game rules, and feedback (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016; Brull & Finlayson, 2016). In addition, Mechanics must be appropriate for the audience, available technology, and learning content. Varying methodologies and tools can make designing and implementing gamification resource prohibitive, highlighting the need for a more streamlined framework (Mora et al., 2017).

This paper will start by discussing an approach that can be used to design a gamification intervention. One component in this approach is game mechanics, which are discussed in more detail after the approach. Finally, the discussion will bring the design and mechanics together with an example.

Design Model

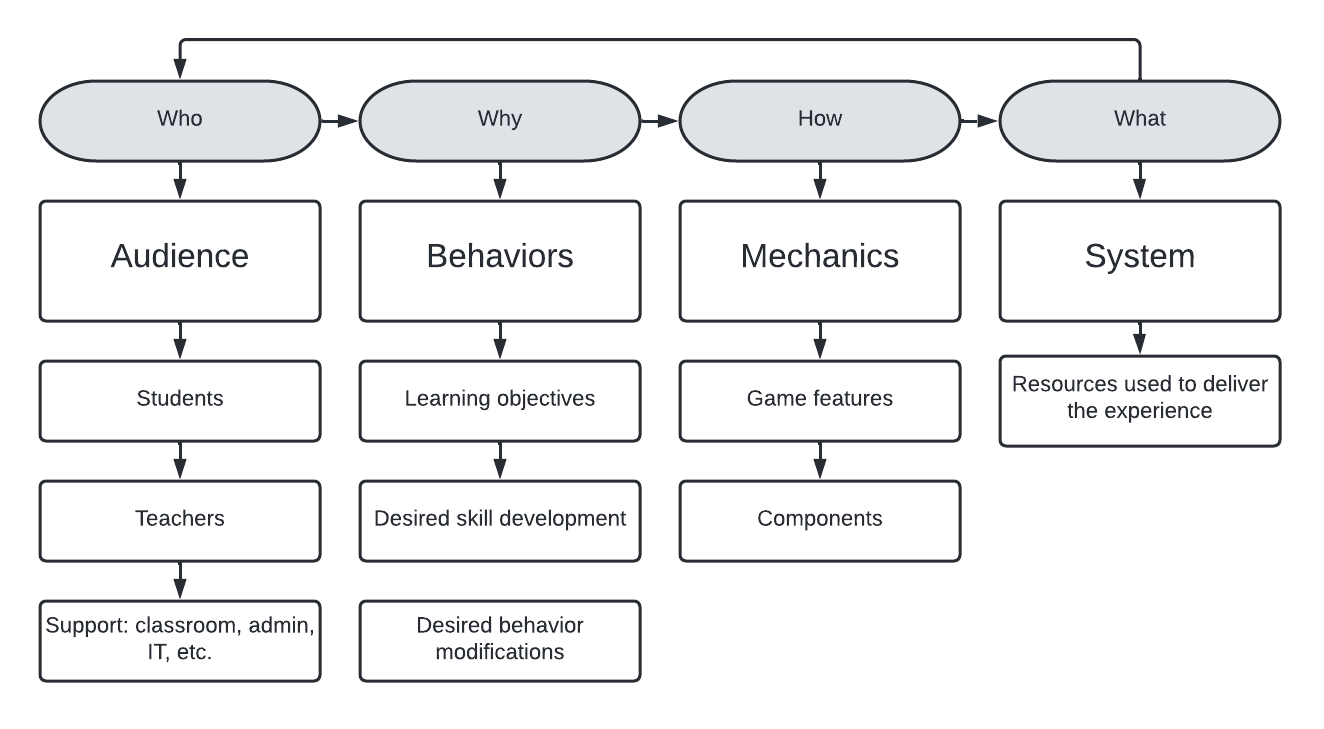

Klock et al. (2015) outlined a conceptual model that included “who, why, how and what” (Diagram 1). “Who” relates to various roles, this could mean students, teachers, or any related support Klock et al., (2015). The student is the priority audience. This group will participate in learning activities, which requires consideration for skill level and learning needs. “Why,” takes desired behaviors into consideration. Klock et al. (2015) mapped out types of behaviors: access content, resolution of exercises and delivery of tasks, increase exercise performance, communication (chat, message board, forums) and frequency of use. “How,” is integrating game mechanics into the learning experience. The next section will discuss game mechanics in more detail. “What,” refers to supporting systems needed to integrate gamification into a learning experience. Consideration should be given to current structures and any changes needed to support the gamification design. For example, the design requires a system that can track progress completion, point accumulation, badges, etc. The supporting system should be part of the initial design process; however, this vast topic extends beyond the scope of this paper. Ideally the gamification experience is designed, and the required resources are implemented. A pragmatic approach might need to accommodate a less than ideal situation. This might require a backwards design approach. Begin the process with assessing available resources and capabilities, then align the design with what is possible.

Diagram 1

Game Mechanics

Mechanics can be described as specific components or game features (Mora et al., 2017). Simões et al. (2013) described game mechanics as “mechanisms” to add a game-like experience to learning activities. The mechanics add that enjoyable aspect of games to a learning experience.

Narrative: A storyline that integrates the theme and mechanics with the learning experience. The story is a mechanism to deliver information, offer guidance, and integrate learning activities (Klock et al., 2015).

Rules: Determination of what can and cannot be done during the gamified experience (Klock et al., 2015). Rules can include guidelines for the game interaction, as well as learning and behavior management. Clear rules can set expectations, guide the learning experience and eliminate potential frustration.

Challenges: Tasks or missions that need to be accomplished, success would result in earning a reward like points (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016). Learning activities can be presented within a context of the narrative to maintain motivation (Klock et al., 2015). Challenges can be used as an assessment to measure learning outcomes.

Points: Used as a scorings system to reward learning progess. These can be awarded as a means to show overall experience or for carrying out a specific task (Klock et al., 2015). The design can incorporate points to illicit desired behaviors, like participation (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016). The environment design could make points visible only to the student (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016) or everyone (Brull & Finlayson (2016). Points provide immediate feedback, shows progress, and offers a way for educators to see if learning outcomes are achieved (Brull & Finlayson (2016). They can be designed to just accumulate or redeemable for awards, to unlock game tools, used for bargaining or redeemed for classroom privileges (Klock et al., 2015).

Levels: Threshold points, that indicate accomplishment of goals (Klock et al., 2015; da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016). Progress through game tasks and point accumulation can trigger a change in level (Brull & Finlayson, 2016). Leveling can be used as a measurement for cumulative learning progress and skill achievement (Klock et al., 2015). Educators can design leveling to coordinate with the end of one learning topic and start of another (Brull & Finlayson, 2016). They should be designed by level of difficulty, meaning early levels related to introductory or basic content and challenges, then concepts gradually build in difficulty (Klock et al., 2015).

Badges: Tangible awards for accomplishing levels (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016), represent an accumulation of points (Klock et al., 2015), or achievement of designated goals. They can be implemented as awards at the end of a level for exemplary work. Brull & Finlayson (2016) look at badges as more of a visual for an associated achievement. da Rocha Seixas et al., (2016) recommends having a place where badges can be displayed. Depending on the age of the audience, they can be viewed as a social components since they can be shared on social media (Brull & Finlayson, 2016). Kim & Castelli (2021) found that in general short-term rewards fostered motivation more than long-term rewards.

Leaderboard: Public scoreboard used to show ranking, based on points accumulation and leveling (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016). A social comparison that can indicate a level of mastery, status, and promote motivation (Kim & Castelli, 2021; Klock et al., 2015). Students see where they are in context to others, motivating healthy competition (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016; Brull & Finlayson, 2016).

Virtual Goods: Digital items that can be purchased with points (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016). They could be used as part of the gamification experience such as tools for trade or as a way to elevate status (da Rocha Seixas et al., 2016). Goods may include items for personalizing the game environment, which offers an opportunity for self-expression (Klock et al., 2015).

Discussion

Mechanics can be applied as part of an integrated design or on an ad-hoc basis. Layering on mechanics will more successfully foster motivation, however, this should be appropriate for the audience, and learning objectives. In determining mechanics consider how the “who, why, how and what” works together (Klock et al., (2015). The “who” or the audience, and the “what” or behaviors have a direct relationship. Learning outcomes will address skills, tasks, or knowledge that should be demonstrated. The “how” or mechanics used should be appropriate for the skill level of the audience, foster learning achievement, and be feasible with system resources. The “what” or system resources should be able to accommodate the mechanics used in the design, accessible to the audience, and have the functionality to foster desired behaviors.

Example scenario

The mechanics and design framework can be applied in a wide range of learning interventions, for learners of all ages. In addition, it can be applied to a full learning path, courses and modules.

Challenge: Pandemic learning suffered some deterioration with student progress, schools consider whether to have a summer break and risk further deterioration, but teachers are tired. One solution, implement a summer reading program, with an age-appropriate educational reading list. This will continue the learning process, and minimize losses typically experienced during summer breaks. The biggest challenge with this type of program is motivating learners to read the books on the list.

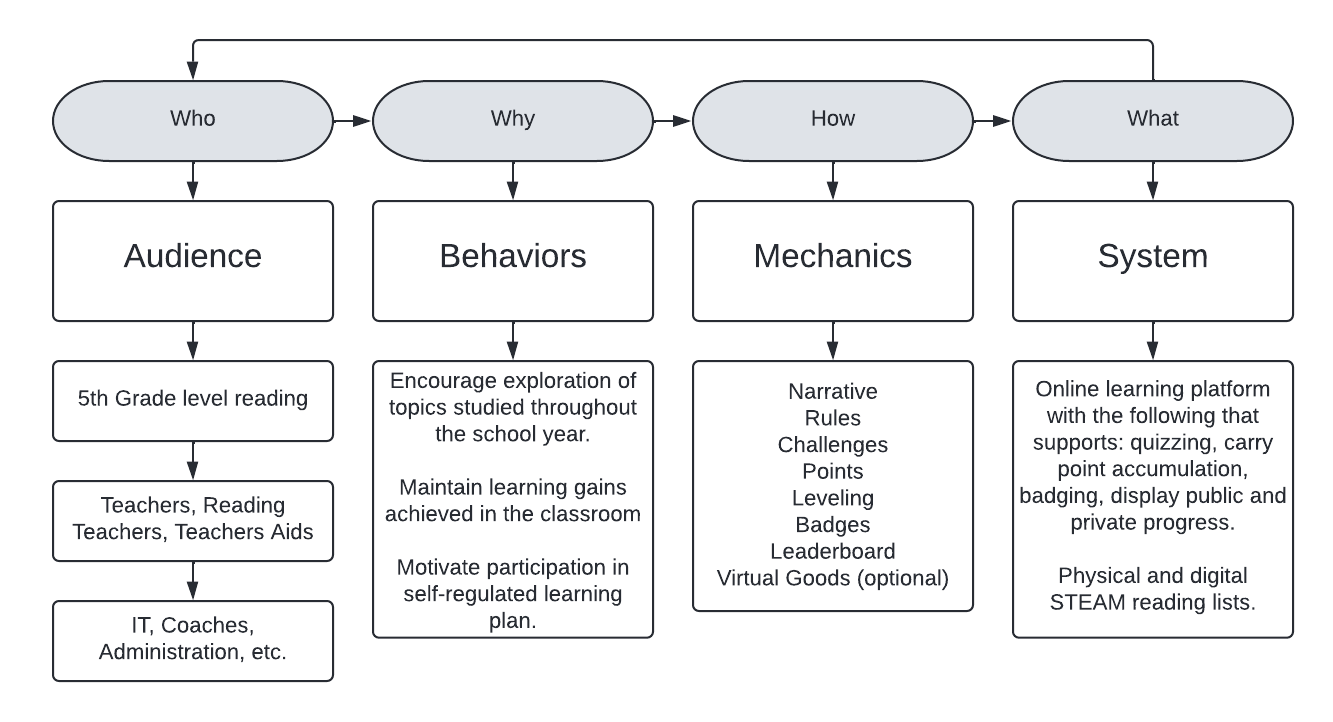

The gamification design should include (Diagram 2):

Who: The primary audience in this example is 5th grade students. The secondary audience includes teachers, reading teachers, aids, administrators and IT.

Why: As setup in the challenge, objectives include: Maintain learning gains achieved in the classroom, encourage further exploration of topics studied throughout the school year, and finally motivate participation in a self-regulated learning plan.

How: The narrative sets up a story of how the main characters found a fossil in their yard. They are trying to identify and determine the age of this fossil. The characters in the story should represent cultures of the student population. All imagery, components and direction aligns with this narrative theme. The rules state that the reading list will provide some help, but clues will be provided after completing challenges. Challenges include completing the reading list, and successfully passing a short quiz about what was read. Points are awarded for completion, with extra points given to quizzes that earn a perfect score. Leveling can be achieved with point accumulation. Badges will be awarded with leveling, and completing reading topic groups (Science, Math, Technology, Art, Social Studies, History, Literature, English). The leaderboard displays the top five students. Virtual goods are optional and can include themed profile stickers, and opportunities to personalize online identities. Although virtual goods do not directly align with the learning goals, they do offer a way to create an inviting environment and represent diversity among students.

What: Age appropriate physical and digital reading lists that cover topics in science, math, technology, art, social studies, history, literature, English. Technology systems include an online learning platform with capabilities to: grade and record quiz questions, accumulated points, and public and private display of progress.

Diagram 2

Additional Considerations

In planning the design considerations should include methods for immediate feedback, opportunities to express achievement, and user customizations. Feedback provides information about progress, supports decision making and promotes guidance to achieve desired behaviors (Klock et al., 2015). Game mechanics that provide feedback are challenges, and reward systems like points and badges. Successful completion of challenges can include positive feedback and next steps, while unsuccessful completion can include hints, and tips to encourage improvement. Achievement could be within a gamified experience, or a classroom (Klock et al., 2015). Recognition for achievement makes the experience more enjoyable. Badges can be used to show achievement outside of the gamified environment. Levels, leaderboards, and virtual goods show achievement within the environment. Customization will allow users to personalize the experience (Klock et al., 2015). Although customizations should be balanced to maintain the integrity of the game, it is a way to make the experience more meaningful to users (Klock et al., 2015). The feasibility of customizations may depend on the system; however, some level of personalization could be integrated into the design with something as simple as themed usernames in the environment.

Conclusion

As remote learning becomes more mainstream educators are faces with new challenges. Motivational tactics used in face-to-face learning needs to be adjusted to an online environment. Gamification can be a solution that motivates learners to log in and maintain engagement with learning materials. Thoughtful design is needed to bridge game mechanics with learning outcomes. This paper offers a design approach outlined by Klock et al. (2015), which included “who, why, how and what.” As exemplified in this paper, this approach can easily adapt to a variety of audiences, learning goals, and available resources. Although the focus was on design and mechanics future discussions would benefit system technologies and adaptable integrations.

There is benefit to practical application of gamification mechanics; however, the body of research would benefit from empirical studies that align design techniques with gamification mechanics, to influence learning. In addition, research would benefit from studies in gamification and self-efficacy among various audiences.

References

Brull, S. & Finlayson, S. (2016) Importance of gamification in increasing learning. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 47, 8.

da Rocha Seixas, L. Sandro Gomes, A., de Melo Filho, I. J. (2016) Effectiveness of gamification in the engagement of students. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 48-63.

Kim, J. & Castelli, D. M. (2021) Effects of gamification on behavioral change in education: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18, 3550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073550

Klock, A. C. T., da Cunha, L. F., de Carvalho, M. F., Rosa, B. E., Anton, A J. & Gasparini, I. (2015) Gamification in e-Learning systems: A conceptual model to engage students and Its application in an adaptive e-Learning system. Gamification in e-Learning Systems, 595–607. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-20609-7_56

Kopcha, T. J., Ding, L. Neumann, K. L. & Choi, I. (2016) Teaching technology integration to K-12 educators: A ‘gamified’ approach. TechTrends, 60, 62–69

Mora, A., Riera, D., Gonza´lez, C. & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2017) Gamification: a systematic review of design frameworks. J Comput High Educ, 29, 516–548.

Simões, J., Díaz Redondo, R. & Vilas, A. F. (2013) A social gamification framework for a K-6 learning platform. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 345–353

Singer, A. (2021, April 14) Online schools are here to stay, even after the pandemic. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/11/technology/remote-learning-online-school.html

Superville, D. (2020, Dec 15) Remote learning will keep a strong foothold even after the pandemic, survey finds. Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/leadership/remote-learning-will-keep-a-strong-foothold-even-after-the-pandemic-survey-finds/2020/12